Category: Math/Science

Josephus Problem

Let’s visualize a solution to Josephus problem. Consider a case of 100 people in circle with person 1 as the starting point, number to be skipped as 2, and elimination in clockwise direction.

So, the survivor is number 73.

Sheldon would be proud.

( ͡° ͜ʖ ͡°)

– Pradeep

The N-Queens Problem

Let’s visualize a solution to the N-queens problem. To keep it simple, let’s solve for a 8×8 chessboard.

This is one of many solutions to the problem.

– Pradeep

Hmmm…🤔

I had this crazy thought when I was a kid.

“Before I die, is it possible to cover every piece of land on this planet just by walking?”

Let’s do a rough math.

If you consider only the landmass, it is 148.94 million sq km. Consider a 1 sq m bounding box. Let’s assume that this box represents our position and moves at 1 sq m per second. Ignore constraints like sleep, food, and crossing the ocean.

To cover the entire landmass, it would take us approximately 4722.85 millenia 😦

– Pradeep

Source :

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/print_xx.html

Visualization : Inspired by the following links

1. http://maxberggren.se/2014/11/27/model-of-a-zombie-outbreak/

2. https://github.com/Zulko/moviepy

Mandelbrot Set

ProTip : Don’t watch Mandelbrot Set infinite zoom video on VR headset for more than 15 minutes.

– Pradeep

References :

1. https://www.ibm.com/developerworks/community/blogs/jfp/entry/How_To_Compute_Mandelbrodt_Set_Quickly?lang=en

2. https://gist.github.com/thr0wn/f80eb02b3e25742aece046f075bb0370

Visualizing Pi Approximation

Approximated using Monte Carlo method.

– Pradeep

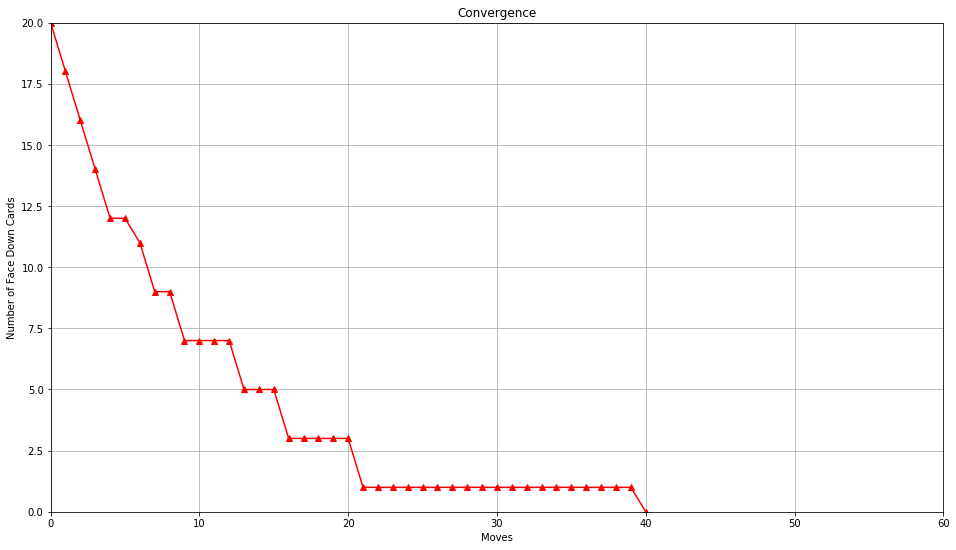

The Twenty Cards Problem

I remember this problem from a movie.

“Twenty random cards are placed in a row, all face down. A move consists of turning a face down card, face up and turning over the card immediately to the right. Show that no matter what the choice of card to turn, this sequence of moves must terminate.”

Solution :

Consider each face down card as a 1 and each face up card as a 0. Initially, your sequence will be 11111111111111111111. Following the rule, each move will create a sequence whose binary value will be lower than the previous sequence. Eventually, all the cards will be facing up.

Let’s do a quick check in Python to verify this logic.

import random

import matplotlib.pyplot as pltCreate a list of 20 1s.

L = [1]*20L : [1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1]

Copy this list so that the original list is undisturbed.

I = L[:]I : [1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1]

Let’s formulate the problem and check if it’s working.

for _ in range(10):

idx = [i for i, x in enumerate(I) if x != 0]

N = random.choice(idx)

if N != 19:

I[N], I[N+1] = 0, 1 - I[N+1]

print(I)

else:

I[N] = 0

print(I)[1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1]

[1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1]

[1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1]

[1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1]

[1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1]

[1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1]

[1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1]

[1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0]

[1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0]

[1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 0]

Now this seems to work. Let’s run this till it terminates.

C = 0

S = [20]

while sum(I)!= 0:

idx = [i for i, x in enumerate(I) if x != 0]

N = random.choice(idx)

if N != 19:

C += 1

I[N], I[N+1] = 0, 1 - I[N+1]

S.append(sum(I))

else:

C += 1

I[N] = 0

S.append(sum(I))

print(C)

print(L)

print(I)40

[1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1]

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

Let’s plot the convergence.

plt.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = [16,9]

plt.grid()

plt.plot(S,'r^-')

plt.title('Convergence')

plt.xlabel('Moves')

plt.ylabel('Number of Face Down Cards')

plt.xlim(0, 60)

plt.ylim(0, 20)

plt.show()

This took 40 moves. In the end, there are no face down cards.

When the same approach was repeated for 100 trials, on an average, it took 42 moves to converge.

– Pradeep

Life and Reinforcement Learning

This article explores the closeness of life, and reinforcement learning, a popular machine learning branch. Although reinforcement learning has grown by drawing concepts, and terminologies from life and neuroscience, I think it’s good to compare reinforcement learning algorithms and life, from which they are derived.

Reinforcement learning is a subset of machine learning which deals with an agent interacting in an environment and learning based on rewards and punishments from the environment. This falls under the broader umbrella of artificial intelligence.

After a group of researchers realized the potential of reward-based learning, a resurgence happened in the late 1990s. Thus, after a number of failed approaches over decades, this interaction and reward-based learning approach seems promising to achieve our dream of artificial general intelligence.

For those who are unfamiliar, this idea is similar to how babies learn to walk.

They make random steps, fall from unstable positions, and finally, they learn to stand upright and walk by understanding the hidden dynamics arising from gravity, and mass. Usually, no positive reward is given to the baby for walking. But the objective is to receive the least negative reward. In this case, least damage to the body while learning to walk.

Trial and error they say.

That does not mean the learning is random. It means that the path to optimal behaviour is not a one-shot solution but happens through a series of interactions with the environment and learning from feedback.

All this happens without higher cognition and reasoning. That’s the power of feedback! The learning is reinforced with the positive and negative feedbacks received from interactions. Once, the optimal behaviour is understood, our brain exploits and repeats the learned behaviour.

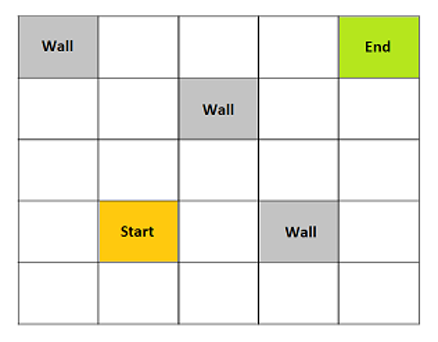

Recently, there has been a number of additions to the existing repository of reinforcement learning algorithms. But to understand the framework of reinforcement learning, there is a popular toy example of optimally navigating in a grid world (say 5×5). The grid world has discrete states with obstacles, a starting point, and a terminal point. The agent is randomly initialized in a state and the goal is to optimally navigate to the terminal state. The agent can take actions such as moving left, right, up, and down. The agent receives a reward of -1 for entering the next state, -10 for hitting the obstacles, and +100 for reaching the terminal state. Thus, the objective is to navigate to the goal position in the shortest possible distance without hitting the obstacles.

This problem, of course, is not difficult to understand and solve. The solution is simple when the value of every state is known. This is a metric that defines how good it is to be in a particular state. Based on this, we can formulate an optimal policy or behaviour.

But how similar is life when compared to this problem of reinforcement learning ?

Much. Except that we don’t have many algorithms, and episodes to establish an optimal behaviour. Essentially, every action in life is about making optimal decision. Given a state, what is the best policy I can follow?

We, as humans, like reinforcement learning agents, are left in a maze like grid world called life. The environment is highly stochastic and time-based. The starting state is biased, and the terminal state is uncertain. By biased starting state, I mean you can either be born in a better place with better opportunities or a worst place with no opportunities. By uncertain terminal state, I mean that death is possible anytime. However, the agents are allowed to make optimistic assumptions throughout the episode.

Before exploring the environment, the first step for the agent is to set the rewards. In reinforcement learning, reward design is usually a tricky process. If the rewards are poorly designed, the agent might be learning something else that is not intended.

How do humans set rewards in their life? Every person has their own way of defining their rewards. In most cases, it is to achieve prolonged happiness or satisfaction by setting goals, sub-goals and achieving them before the episode ends. Most humans follow hedonistic approach by setting immediate pleasures as their rewards. But focusing only on the short-term immediate rewards may not result in an optimal policy in the long run.

But what policy to follow when the agent has defined a goal? Exploit or Explore or combinations? What about the ethical issues that arise while following a policy? What is right and wrong? No one knows. As said before, no one has a golden algorithm for these questions. The environment is highly stochastic where even the episode length, and terminal state are uncertain.

Some agents look far into the future, estimate the value function of each state regularly, and formulate their policy accordingly. They understand the importance or value of every stage of life, and take the optimal action. They exploit, and reach their goals before the end of episode, and receive a huge positive reward. Success, they call it.

Some agents take this success to the next level by finding the exact explore-exploit trade-off point. In addition to the known rewards, they discover rewards that were previously unknown to the agents who just exploit.

Unfortunately, many agents keep exploring the environment without understanding the importance of goal setting, and value function estimation. They make random moves, keep hitting the obstacles, and die without a policy towards the goal state. Their episode ends with a high negative reward.

Most agents achieve partial success by reaching a sub-optimal point. They manage to achieve few sub-goals but fail to reach their goals by making wrong assumptions, incorrect value function estimation, and by the wrath of stochasticity of the environment. Something is better than nothing, they say.

But is it possible to formulate a global optimal behaviour for this environment?

I don’t think so. The large number of hidden factors contributing to the stochasticity of the environment makes it really hard to come up with a single golden policy which assures success.

And the worst part, unlike the reinforcement learning agent, which runs millions of episodes to learn an optimal behaviour, we just have one episode.

Yes, only one. That’s unfair. But the good part is, you can learn from the episodes of other agents. If you are willing to.

– Pradeep

Image Sources :

1. http://pavbca.com/

2. https://unsplash.com/

Further Reading :

Reinforcement Learning : An Introduction – Richard S. Sutton and Andrew G. Barto